Donna Brazile writes in Ms. magazine that in the elections of 2008 and 2012, the group that turned out to vote in the highest numbers was black women. In 2012, 60 percent of 18- to 29-year-old-black women voted, and 76 percent of all black women were registered to vote. A recent Pew study found that in 2012, the voter turnout in the United States was low—53.6 percent of the estimated voting-age population. Only 65 percent of the US voting-age population even bothered to register to vote.

Brazile cites “The Power of the Sister Vote” poll from Essence magazine, which indicates that the turnout will again be strong for black women in 2016, “driven by a hunger to institutionalize their gains” in:

Donna Brazile writes in Ms. magazine that in the elections of 2008 and 2012, the group that turned out to vote in the highest numbers was black women. In 2012, 60 percent of 18- to 29-year-old-black women voted, and 76 percent of all black women were registered to vote. A recent Pew study found that in 2012, the voter turnout in the United States was low—53.6 percent of the estimated voting-age population. Only 65 percent of the US voting-age population even bothered to register to vote.

Brazile cites “The Power of the Sister Vote” poll from Essence magazine, which indicates that the turnout will again be strong for black women in 2016, “driven by a hunger to institutionalize their gains” in:

- Increased affordable health-care access

- Quality education reform and access to low-cost college education

- Living-wage reforms

- Criminal justice reforms

But the frustration levels are high for political candidates like Donna Edwards, an African American woman who just lost the Democratic primary race for a Senate seat in Maryland. Jill Filipovic writes in the

New York Times that while the Democrats rely on black female voters, only one black woman has ever been elected to the Senate. In addition, while Trump accuses Clinton of playing the “woman card,” Edwards, during her primary race, was accused of playing both the “woman card” and the “race card.” The implication is that these “cards” somehow confer unearned advantages to the women holding them. Yet

research shows that for black women, combined stereotypes about both race and gender create double challenges for them to be perceived as competent leaders and elected, or hired, to leadership positions.

Filipovic suggests that the problem, in general, is that authority, competence, and power are perceived to be male qualities. Several recent studies show that when the same résumés are shown to both male and female evaluators, the documents are rated more highly when they have a man’s name, John, on the top than when the same documents have a woman’s name, Jennifer, at the top.

Filipovic proposes that to fight pervasive prejudices, we need to change our images of competence and power by putting more women, especially more women of color, into positions of authority and leadership so that women in authority becomes normal rather than unusual. Specifically, she says, “we can’t change longstanding assumptions about what a leader looks like unless we change what leaders look like. . . . Democrats should make [the ‘woman card’ and the ‘race card’] central components of a winning hand.” She also suggests that when there are equally qualified men and women competing for positions, Democrats should champion politicians who are not white men. It’s the only way that, in the long run, we are all going to win.

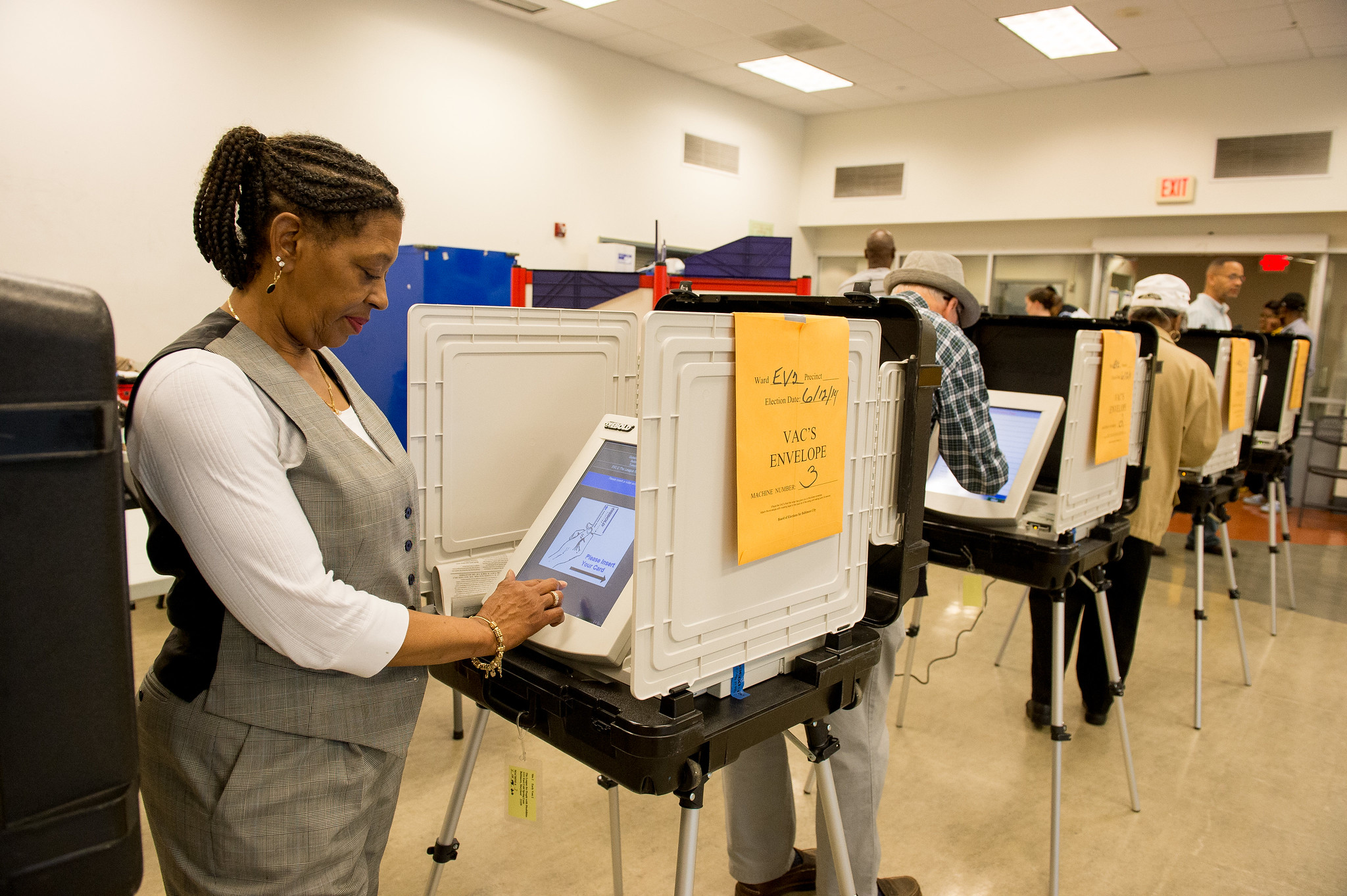

Photo credit: Governor Votes Early. by Jay Baker at Baltimore, MD. via

Maryland GovPics on Flickr]]>

Donna Brazile writes in Ms. magazine that in the elections of 2008 and 2012, the group that turned out to vote in the highest numbers was black women. In 2012, 60 percent of 18- to 29-year-old-black women voted, and 76 percent of all black women were registered to vote. A recent Pew study found that in 2012, the voter turnout in the United States was low—53.6 percent of the estimated voting-age population. Only 65 percent of the US voting-age population even bothered to register to vote.

Brazile cites “The Power of the Sister Vote” poll from Essence magazine, which indicates that the turnout will again be strong for black women in 2016, “driven by a hunger to institutionalize their gains” in:

Donna Brazile writes in Ms. magazine that in the elections of 2008 and 2012, the group that turned out to vote in the highest numbers was black women. In 2012, 60 percent of 18- to 29-year-old-black women voted, and 76 percent of all black women were registered to vote. A recent Pew study found that in 2012, the voter turnout in the United States was low—53.6 percent of the estimated voting-age population. Only 65 percent of the US voting-age population even bothered to register to vote.

Brazile cites “The Power of the Sister Vote” poll from Essence magazine, which indicates that the turnout will again be strong for black women in 2016, “driven by a hunger to institutionalize their gains” in: